Or as Ken Hillis puts it, “the body-as-object (and by extension humanity) becomes subject to, even inscribed by, the laws of technique that are intended to render nature more subject to human control.” 8 The Rationalization of Vision

Yet it is this disembodied and rationalized mode of perception that increasingly prevails and imposes itself on the human sensorium. The roving, binocular, and psychologically conditioned sight of humans is substituted for a fixed, monocular, and strictly geometric gaze. Neither perspective nor its associated machines faithfully replicate human vision, of course.

From the outset, perspective participated in an objectivization of perception, no longer solely residing in phenomenological embodiment but instead now the outcome of a systematic application of “a rational and repeatable procedure.” 7 Moreover, this algorithmic apprehension of perception made possible its comprehensive mechanization and relocation within new socio-technical assemblages. If optically consistent visualizations have decisively contributed to the success and proliferation of modern scientific practices, they can be considered more generally as instruments of power for shaping the natural and social world. 5 While these properties do not flow exclusively from it, linear perspective is nonetheless paradigmatic by virtue of “its logical recognition of internal invariances through all the transformations produced by changes in spatial location.” 6 These new itinerant forms of inscription not only serve as repositories of accumulated knowledge but as material anchors for the cognitive operations necessary to the emergence and sustenance of a modern scientific culture.

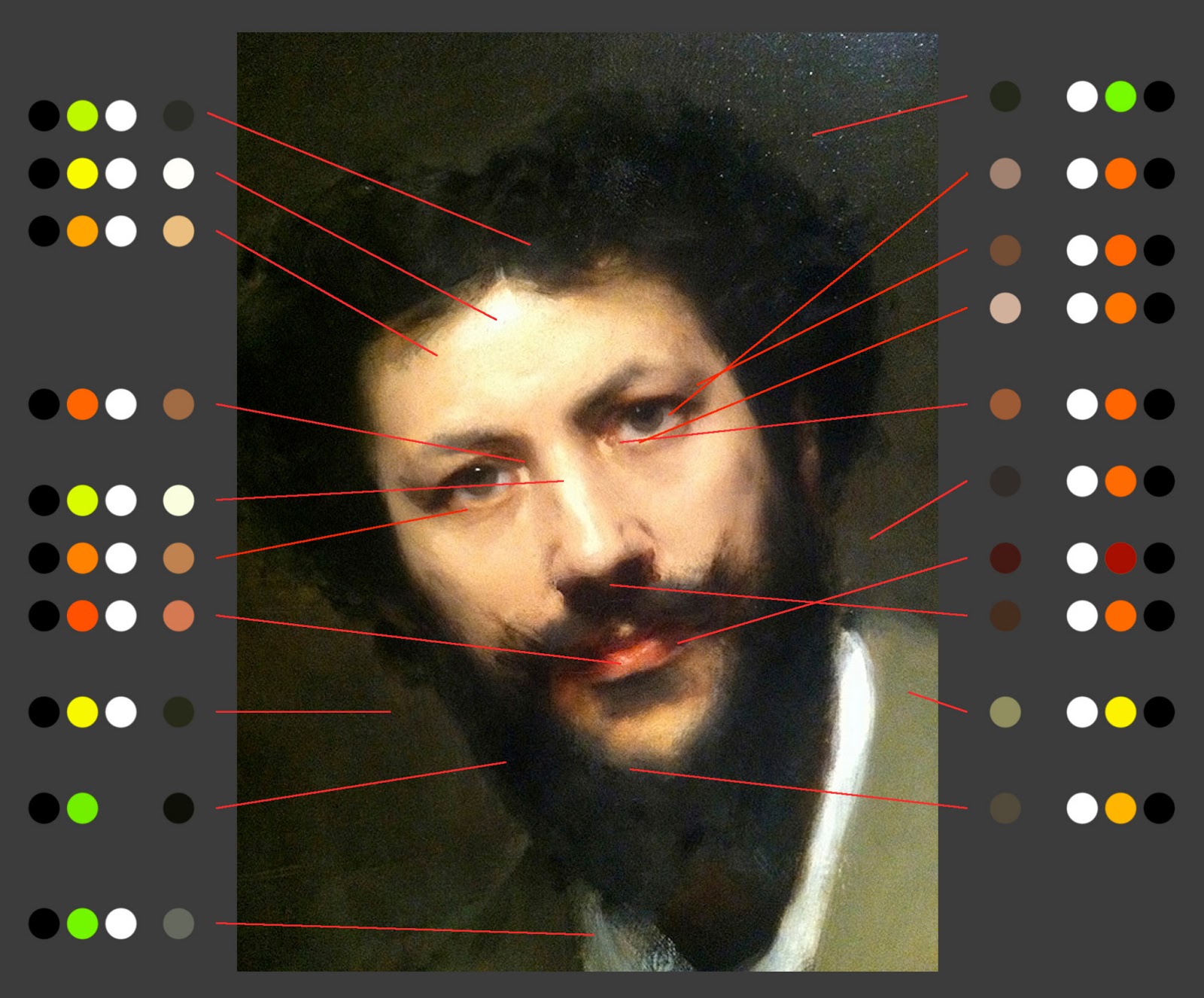

Common to linear perspective, scientific mapping, and technical drawings, optical consistency permits the description of physical spaces and objects in a systematic geometric fashion that facilitates the circulation of these representations and allows for “the possibility of going from one type of visual trace to another.” 4 These particular representations possess, for Latour, the character of “immutable mobiles” able to disseminate widely and undergo rule-bound transformations and additions without losing or distorting their valuable informational content. 2 For William Ivins, perspective offers in this way a “practical means for securing a rigorous two-way, or reciprocal, metrical relationship between the shapes of objects as definitely located in space and their pictorial representations.” 3 Bruno Latour further points to the paramount importance of the “optical consistency” found in Renaissance techniques of visualization for the development of modern scientific culture. In ordering visual space according to “an abstract uniform system of linear coordinates,” perspective binds subjective perception and objective spatial extension through mathematical convertibility.

And in common with the field of cartography emerging at the same time, perspective employs a system of geometric projection of a three-dimensional space upon a two-dimensional surface in a manner that preserves the space’s relative proportions and the objects contained within. automatable) construction of images that convey an optically convincing depiction of physical space follows from it. A rigorous procedure for the rule-governed (i.e. At its heart is a geometric conception of vision that accounts for the natural ocular estimation of spatial distances and begets an array of mathematical techniques and associated instruments for precise measurement by the human eye. Much more than a mere internal development within the history of art, linear perspective sits at the confluence of the fields of geometrical optics, pictorial representation, and land surveying. Figure 1: Pietro Perugino, Christ Giving the Keys to St.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)